Read here the official article on ARTRIBUNE (Ita)

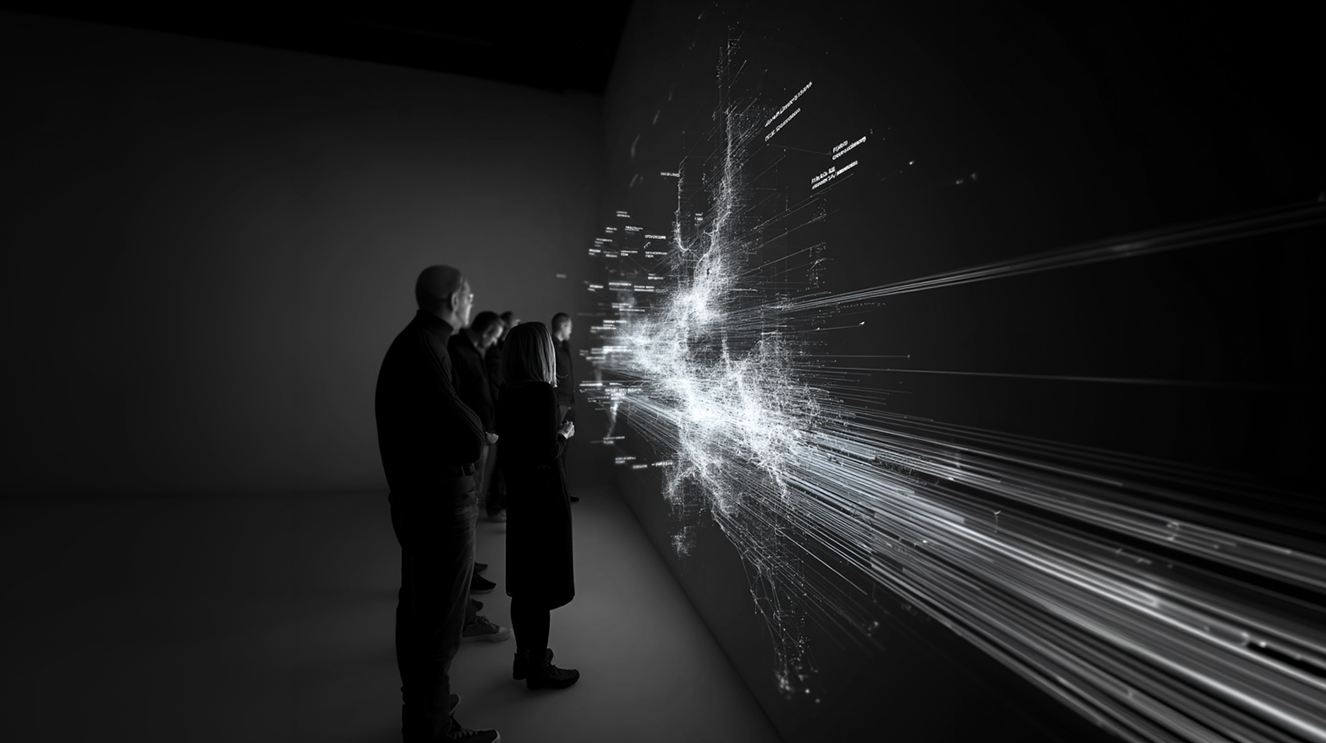

You step into an exhibition and you feel it instantly: the work lives in the rhythm by which space conducts you. A threshold slows you down, a light shifts your attention, a sound “anchors” you to your body, a sequence of images imposes a duration. The work takes shape as a perceptual condition—a field that organizes experience, memory, and meaning.

This idea has a precise genealogy. Umberto Eco, with The Open Work (Opera aperta, 1962), describes an artwork capable of hosting multiple interpretations and plural pathways: a structure that generates meaning through activation and reading. From here, a continuous line unfolds within contemporary art: idea, instruction, process, relation, system. A line that today finds in generative AI a natural accelerator. To explore Eco’s thinking on art further, see the article Umberto Eco: Between Art, Philosophy, and Aesthetics.

The Turn Toward “Fields” and the System Mode

Jack Burnham, in “Systems Esthetics” (Artforum, 1968), identifies a growing polarity between the unique artwork and “unobjects”: environments and artifacts with systemic behavior, capable of challenging traditional categories of criticism. This intuition resonates strongly today: many contemporary works operate through ecologies of interdependent components.

Inside the work-as-system we find:

- technology (screens, software, pipelines, algorithms)

- space (pathways, thresholds, distances, scales)

- time (loops, versions, updates, archives)

- institution (display, mediation, communication, commissioning)

- public (presence, choice, attention, participation)

Meaning emerges from the composition of these elements. The work becomes an organism: a set of rules and consequences.

Instructions, Constraints, Decisions: The Idea as Engine

Sol LeWitt, in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967), formulates a principle that feels strikingly current: the idea as engine, the project as a device capable of generating the work. In parallel, Lucy R. Lippard, with Six Years (1973), documents “dematerialization” through a shift toward language, documentation, exchange networks, and conceptual practices.

Here a direct bridge opens toward the generative: authorship manifests in the design of constraints and in the quality of decisions. AI becomes a laboratory of possibilities that demands direction. The operational chain takes on a clear form:

intention – constraints – iteration – selection – editing – context → reception

The work is recognized in the method and in the structure that sustains it.

Prompt / Score: Writing That Produces Reality

Fluxus pushes this logic into radical territory: event, instruction, activation. Tate presents Fluxus as an international avant-garde collective born and flourishing in the 1960s, capable of moving across media and disciplines.

Within this constellation, Grapefruit by Yoko Ono (1964) becomes a perfect reference: a collection of “instruction works” and “event scores,” works that exist through indications to be activated in mind and world.

In the generative field, the prompt operates in this direction: a score. It defines a field of variations, organizes a language, builds a grammar. Value emerges from the precision of the writing, the coherence of constraints, and the ability to give birth to a family of outcomes that “speak to one another.”

Process in the Foreground: Versions, Transformations, Editing

Process art places process at the center: Tate defines it as art in which the making of the work remains a prominent aspect of the result. This framework offers an effective vocabulary for reading generative practice: versions, attempts, discards, selections, editing. The work often coincides with the curve of labor, the trajectory of decisions, the discipline of montage.

In an ecosystem of iterations, the curve becomes visible: rhythm, sequence, density, the quality of the cut. The work-as-system calls for an artist who is editor and designer—capable of extracting meaning from multiplicity.

Event, Public, Activation: Participation as Working Material

Allan Kaprow’s Happenings open a decisive door: the event as a situation in which environment and audience participate in the construction of meaning. Tate recalls 18 Happenings in 6 Parts (1959) among the key moments for a broader public. MoMA places happenings among the precursors of performance art, highlighting the shift toward actions and contexts.

This line leads to participatory practices: MoMA defines participation and audience involvement as the opening of the creative process to others, with a redistribution of control and authorship.

When a contemporary work constructs an immersive environment, an audiovisual sequence, an experiential room, the public becomes a structural component. The work manifests as a situation: a perceptual engine that requires presence.

Aesthetics of Sociality: Relation Given Form

In the 1990s, Nicolas Bourriaud formulates relational aesthetics: Tate presents it as a tendency oriented toward producing works based on human relations and social context. MoMA emphasizes the creation of spaces and situations dedicated to social interactions.

This perspective helps read many contemporary practices: devices for encounter, negotiation, micro-rituals, shared reception. In a present organized by platforms, feeds, and attention circuits, the work-as-system also operates on how we are together inside an experience.

Display, Power, Infrastructures: The Institution Enters the Work

Institutional critique makes another layer explicit: the institution enters artistic operation. Tate defines it as a practice focused on the critique of museums and galleries.

MoMA situates it among forms of conceptual art emerging in the late 1960s, oriented toward the mechanisms of art institutions. Today this layer expands toward infrastructure: platforms, standards, policies, datasets, distribution systems. The work-as-system absorbs the technical and cultural environment in which it circulates—and the artist also works on the governance of the visible.

Network and Feedback: A Telematic Trajectory

Art history offers another extremely useful root: telematics. Telematic art is described as a practice that uses telecommunications networks as a medium and builds interactive contexts; Roy Ascott appears among the central figures, with a vision of the work as process and distributed participation. This genealogy brings to the surface a key theme of today: the work understood as a circuit of feedback, exchange, and updating.

Generative AI enters here naturally: model, artist, audience, and platforms arrange themselves as nodes within an ecosystem. The quality of the work emerges in the ability to design this field: rules, rhythms, editing, thresholds, intensities.

The Work-as-System Laboratory: How an Operative Field Is Born

In my own experimental practice as a generative artist, the work does not coincide with a single output: it coincides with the grammar that makes it possible and with the field that makes it happen. I work through protocols, prompts, constraints, datasets, editing, display—as if they were a score—because that is where the identity of the work is established. Every image, every soundscape, every video performance is a provisional matrix; every variation is a test; every sequence is a perceptual choice. I don’t choose the “best” result: I build a generative framework that produces meaning through repetition, feedback, and context. In this way, collaboration with AI is not a special effect, but a mode of construction: an operative field in which form, time, and continuous reworking are, in fact, fundamental parts of the work.

Dario Buratti

www.darioburatti.com

References

- Eco, Umberto (1962). The Open Work (Opera aperta). Monoskop (PDF). https://monoskop.org/images/6/6b/Eco_Umberto_The_Open_Work.pdf

- Burnham, Jack (1968). Systems Esthetics. Artforum. Monoskop (PDF). https://monoskop.org/images/0/03/Burnham_Jack_1968_Systems_Esthetics_Artforum.pdf

- LeWitt, Sol (1967). Paragraphs on Conceptual Art. Monoskop (PDF). https://monoskop.org/images/3/3d/LeWitt_Sol_1967_1999_Paragraphs_on_Conceptual_Art.pdf

- Lippard, Lucy R. (1973). Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. Monoskop (PDF). https://monoskop.org/images/0/07/Lippard_Lucy_R_Six_Years_The_Dematerialization_of_the_Art_Object_from_1966_to_1972.pdf

- Tate. Fluxus (Art Term). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/f/fluxus

- Wikipedia. Grapefruit (book) (Yoko Ono, 1964). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grapefruit_%28book%29

- Tate. Process art (Art Term). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/process-art

- Tate. The Happening (Art Term). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/h/happening/happening

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Happenings (Collection Terms). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/happenings

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Participation and Audience Involvement (Media and Performance Art / Collection Terms). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/media-and-performance-art/participation-and-audience-involvement

- Tate. Relational aesthetics (Art Term). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/r/relational-aesthetics

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Relational aesthetics (Collection Terms). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/relational-aesthetics

- Tate. Institutional critique (Art Term). https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/i/institutional-critique

- The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Institutional critique (Collection Terms). https://www.moma.org/collection/terms/institutional-critique

- Wikipedia. Telematic art. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telematic_art